The ‘Sequential Intercept Model’ – a trauma-informed diversionary framework

Foreword

HM Inspectorate of Probation is committed to reviewing, developing and promoting the evidence base for high-quality probation and youth justice services. Academic Insights are aimed at all those with an interest in the evidence base. We commission leading academics to present their views on specific topics, assisting with informed debate and aiding understanding of what helps and what hinders probation and youth justice services.

This report was kindly produced by Dr Suzanne Mooney, Dr Stephen Coulter, Professor Lisa Bunting and Dr Lorna Montgomery, introducing the ‘Sequential Intercept Model’ (SIM) which was originally developed in the USA as a cross-systems framework to consider the interface between the criminal justice and mental health systems. They highlight how the SIM can be used more widely as a trauma-informed framework which identifies key stages and opportunities for diverting children and adults with complex needs from the criminal justice system or from penetrating deeper into the system. Looking across the stages – termed ‘intercepts’ – there are a number of key messages, including the importance of cross-systems collaboration and service co-ordination, the need for appropriate information-sharing within and between agencies and services, and the benefits from strengthening positive relationships around the individual. It is concluded that with concerted collaborative efforts, there are opportunities to improve the life chances of children and adults by ensuring earlier access to the services required to meet their individual needs.

Dr Robin Moore

Head of Research

Author profiles

All authors are academics in the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast. While each has differing specialisms, collectively they have been involved in a range of practice and research initiatives related to the implementation of trauma-informed approaches (TIA) across justice, child welfare, health, social care and education sectors and the associated evidence of effectiveness. Dr Mooney is currently leading a team undertaking a cross-sector organisational review of trauma-informed implementation as a means of sharing transferable learning and envisioning the next steps for TIA advancement in Northern Ireland.

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the policy position of HM Inspectorate of Probation

Introduction

1.1 Trauma-informed justice systems

This paper is drawn from an original report (Mooney et al., 2019) commissioned by the Safeguarding Board Northern Ireland as part of a cross-departmental initiative to support the development of trauma-informed practice in Northern Ireland. The original report used the ‘Sequential Intercept Model’ or SIM as a framework to undertake a selective review of practice innovations at different stages of the justice process as a means to consider how to divert young people and adults with complex needs from the criminal justice system (CJS).

Awareness of the SIM had emerged from a rapid evidence review which had summarised the evidence relating to the implementation of trauma-informed practice across multiple systems and settings (child welfare, health, education), including justice (see Bunting et al., 2018a-e; Bunting et al., 2019). International recognition of the strong connections between a trauma history and involvement with the justice system (Bellis et al., 2015), continued traumatic experiences within the justice system (Kubiak et al., 2017), and the relationship between harsh punishments and continued offending (Ko et al., 2008) has led to the adoption of trauma-informed approaches in secure settings both internationally and in the UK (e.g. D’Souza et al., 2021). Although not specifically named by its developers as a trauma-informed approach, the SIM was identified as a promising framework promoted by the US federal government Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration Agency (SAMHSA), highlighting opportunities to implement community-based intervention for justice-involved individuals suffering mental ill health and/or substance use as a means of minimising CJS involvement (Munetz and Griffin, 2006, p.320). It is argued that such diversion has the potential to reduce costs to society and deliver appropriate services without increasing the risk to public safety (Heilbrun et al., 2015).

1.2 Justice-involved persons with complex needs

It is well established in international literature that young people and adults involved with the justice system are disproportionately affected by adversity and trauma (Miller et al., 2011), with exposure to childhood adversity identified as a key risk factor for subsequent justice involvement (Kerig and Becker, 2010; Bellis et al., 2015). UK research indicates the scale of the increased risk with population-based adverse childhood experience (ACE) surveys demonstrating that English adults exposed to four or more ACEs were 11 times more likely to be imprisoned at some time in their lives (Bellis et al., 2014) while Welsh adults experienced a 20 times greater likelihood in comparison to adults with no ACEs (Bellis et al., 2015). More recently, research in Manchester found that justice-involved children typically had multiple ACEs (see Academic Insights paper 2021/13 by Gray, Smithson and Jump). The complex links between health, social inequality and crime are also increasingly recognised (for example Public Health England, 2018) with justice-involved persons known to suffer significantly worse health than the general population and more likely to be the victims of crime (Anders et al., 2017).

Although much of the US SIM literature refers specifically to people impacted by ‘mental health and substance use disorders’, this paper uses the overarching term of persons with ‘complex needs’ to better capture the range of adversities common in justice-involved young people and adults. These include: different forms of abuse; family breakdown and care experience; domestic violence; homelessness; lack of education and employment; as well as mental ill health and substance use problems (see Table 1). UK policy developments have recognised these challenges with adult and youth justice processes striving to take account of these intersecting influences on offending behaviour and promote cross-sector partnership to enable upstream intervention to prevent or mitigate the underlying causes of offending (see, for example, Public Health England, 2018; Department of Health and Department of Justice, 2019).

| Characteristic | Adult prison Population | General population |

|---|---|---|

| Taken into care as a child | 31% of women 24% of men |

2% |

| Experienced abuse as a child | 53% of women 27% of men |

20% |

| Observed violence in the home as a child | 50% of women 40% of men |

14% |

| Expelled or permanently excluded from school | 32% for women 43% for men |

In 2005 >1% of school pupils |

| No qualifications | 47% | 15% of working age population |

| Never had a job | 13% | 4% |

| Homeless before entering custody | 15% | 4% |

| Have symptoms indicative of psychosis | 25% for women 15% for men |

4% |

| Identified as suffering from both anxiety and depression | 49% for women 23% for men |

15% |

| Have attempted suicide at some point | 46% for women 21% for men |

6% |

| Have ever used Class A drugs | 64% | 13% |

In addition to the prevalence of a trauma history for individuals prior to their involvement with the CJS, the potential for the justice process itself to evoke a trauma response is well evidenced and widely accepted (Kubiak et al., 2017; see also Academic Insights paper 2023/09 by Kilkelly). Trauma triggering experiences may occur in the innumerable interactions and processes that make up the justice pathway. While practices frequently utilised in justice settings may be considered necessary to maintain order, manage challenging behaviours and increase safety for staff and others (particularly within custodial establishments), these interpersonally restrictive practices are recognised as potentially traumatic in their own right, and can have a re-traumatising effect on people impacted by early life trauma (Baker et al., 2022; Cusack et al., 2016).

The Sequential Intercept Model: best practices across the intercepts

2.1 The ‘Sequential Intercept Model’

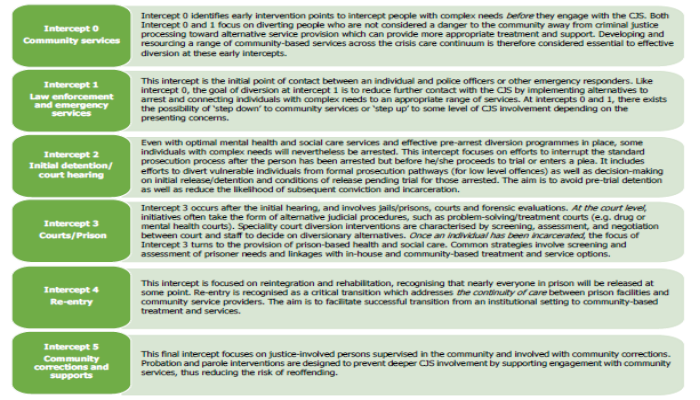

The ‘Sequential Intercept Model’ or SIM was developed in the USA (Policy Research Associates, 2018) as a cross-systems framework to consider the interface between the criminal justice and mental health systems. It has been utilised as a strategic planning tool to assess available resources, determine service gaps, identify opportunities, and develop priorities for action to improve system and service-led responses focused toward adults with mental health and substance use problems who are involved with the CJS. The SIM is premised on the recognition that the CJS is often ineffective at meeting the multi-faceted needs of people with complex needs, and that justice involvement itself can exacerbate existing difficulties, inadvertently increasing the likelihood of reoffending (Munetz and Griffin, 2006).

The SIM has undergone years of piloting and refinement. The original model delineated five intercepts (labelled 1 to 5) corresponding to key criminal justice processing decision points: law enforcement; initial detention/initial court hearings; jails/courts; re-entry; community corrections. An additional intercept (Intercept 0 ‘community services’) was formally introduced in recognition of the dual roles played by the police in protecting public safety and serving as emergency responders to people in crisis (Abreu et al., 2017). Police officers and emergency services therefore form an essential part of the ‘crisis care continuum’.

It is argued that these six decision points represent junctures where people could be prevented from ‘entering or penetrating deeper into the criminal justice system’ (Munetz and Griffin, 2006, p.544) and diverted to alternative services that are more appropriate to their needs. Each intercept therefore functions as a filter, with interventions ideally ‘front-loaded’ to ‘intercept’ people early in the pathway (Willison et al., 2018) and thus curtail criminal justice involvement to its lowest level.

2.2 Key messages

This section examines the key messages across all SIM intercepts, including the best practice principles developed by SIM advocates as well as two additional overarching themes identified in the literature reviewed. For further information on practice innovations relating to each of the distinct intercepts, please see the full report (Mooney et al., 2019).

Key message 1 – cross-systems collaboration and service co-ordination

Collaborative and co-ordinated efforts across systems and services are identified as essential to avoid justice-involved persons with complex needs falling through the inevitable gaps that emerge when multiple service providers do not take shared responsibility for the person’s welfare and commit to working together to this end. It is noted as essential for effective outcomes that co-ordinating bodies develop ‘community buy-in’ through shared identification of priorities, funding streams and accountability mechanisms (Policy Research Associates, 2018). It is in this regard that the SIM ‘mapping process’ has been developed as an important strategic planning tool to bring stakeholders and communities of interest together to engage in facilitated mapping exercises to consider the pathway of justice-involved persons through the CJS, assess available resources, determine service gaps and develop shared priorities for action (Willison et al., 2018). Emerging evidence confirms that this mapping process has been well-received and has led to enhanced cross-sector collaboration and co-ordination (Bonfine and Nadler, 2019).

Key message 2 – information-sharing and performance measurement

Appropriate information-sharing within and between agencies and services is deemed essential to achieve consistent and effective cross-system collaboration and co-ordination to better meet the multi-faceted basic health and social care needs of justice-involved persons (such as safe accommodation and access to primary healthcare) as well as targeted treatment and support for specific mental health conditions or substance use issues (Policy Research Associates, 2018). This requires the development of information-sharing protocols and memoranda of understanding between interfacing service providers and training for personnel to understand their responsibilities in order to achieve the recommended ‘warm handovers’ as a person transitions between services.

It also demands a commitment to performance measurement as a means of identifying, gathering, analysing and applying relevant data to inform service developments (GAINS, 2019). It is noted that efforts to share data can fail when stakeholders lack clarity on the most essential information to collect, integrate and examine (GAINS, 2019). It is recommended that aggregate data should be gathered and shared between relevant agencies to understand the volume of people requiring access to specific services to help identify gaps or insufficiencies in service provision. Each chapter in the original report (Mooney et al., 2019) highlighted some of the common variables and measures that could be collected at each intercept. Additionally, it is noted that identifiers may also be used to track individuals as they move through the intercepts. Such processes will assist identification of ‘super-utilisers’, providing a better understanding of their specific needs, identifying service gaps and promoting tailored, joined-up service provision (Policy Research Associates, 2018).

Key message 3 – routine identification of complex needs

At each intercept, there is a need for routine identification of people with complex needs, including mental health and substance use issues as well as other issues identified as common in justice-involved persons (such as adverse childhood experiences, trauma, domestic violence, care experience, homelessness). It is recommended that individuals with mental health and substance use conditions should be identified through the routine administration of validated screening instruments (Policy Research Associates, 2018). Routine identification is noted to require different forms of assessment at different stages in the criminal justice process and may be conducted by different professions or services. Such early identification is understood as essential to enable follow-up assessment and the provision of services and targeted treatment to meet identified needs. Early identification of complex needs will also be assisted by appropriate information-sharing between services and agencies. It should be noted however that routine enquiry into people’s adverse life histories requires due care, skill and consideration to avoid re-traumatisation. Clarity is required for frontline practitioners about why and how routine screening information will be used; what information will be shared and with whom; and how to discuss immediate or ongoing need (see Akin et al., 2017; Lang et al., 2017; Quigg et al., 2018 for learning from child welfare and mental health contexts).

Key message 4 – links to healthcare and social support services including housing

This best practice principle reminds service providers of the need to ensure justice-involved persons across all intercepts have appropriate access to basic health, social care and financial supports including social security, safe housing and social supports in the community. Without such basic supports, it is unlikely that targeted mental health or substance use treatments alone will be effective in helping individuals avoid further CJS interaction. The literature reviewed makes consistent reference to housing as a key priority for successful diversion (DeMatteo et al., 2013; Heilbrun et al., 2015; Shaw et al. 2017; Yuan and Capriotti, 2019). This is mirrored in the UK context where having and retaining settled accommodation is noted by inspectors as ‘a key factor in successful rehabilitation’ (HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2020). The exclusion of justice-involved persons leaving prison from public housing and employment opportunities has been referred to as ‘invisible punishment’, which is proposed by some to be as severe as the prison sentence itself (Mauer and Chesney-Lind, 2002), increasing the likelihood of reoffending.

Key message 5 – strengthening supportive relationships with family and extended others

Although not mentioned specifically as an over-arching best practice principle in the US SIM literature, Mooney et al. (2019) concluded that intervening to strengthen supportive informal relationships should feature as an essential component of trauma-informed practice initiatives across all six intercepts given its significance in the practice literature reviewed. Involving supportive family, friendships and significant others is recognised to assist successful engagement of vulnerable children and adults with an appropriate range of heath and social care service provision prior to or upstream in their involvement with the CJS (Farmer, 2019). Positive relationships and family contact are also known to influence how justice-involved persons cope with imprisonment as well as their reintegration and rehabilitation upon release and are strongly associated with reduced risk of reoffending (Markson et al., 2015).

This best practice key message is in keeping with the Ministry of Justice reviews which have highlighted the importance of strengthening family ties to prevent reoffending and reduce intergenerational crime (Farmer, 2017; 2019). Lord Farmer’s report (2017) on the importance of strengthening male prisoners’ family relatonships drew attention to a landmark study which found that 63 per cent of male prisoners’ sons went on to offend themselves (Farrington et al., 1996). A subsequent parallel review on female offenders’ family relationships (Farmer, 2019) cited research which found that adult children of imprisoned mothers were more likely to be convicted than adult children of imprisoned fathers (Dallaire, 2007) as well as noting that ‘a large proportion of female offenders have endured domestic and other abuse, often linked to their offending’ (Farmer, 2019, p.7).

Both reports described the importance of supportive family and other relationships as the ‘golden thread’ through all processes in the CJS – from early intervention to community solutions (see Academic Insights paper 2021/02 by Trotter) and better custody for those who must serve a custodial sentence – with calls for action across several government departments. Lord Farmer concluded that systems of care (whether justice, health or social care) ‘cannot waste any opportunity to capture information about a woman’s family and relational background, including her children and other relationships which may be supportive’ (2019, p.9).

Key message 6 – including peers with lived experience

The inclusion of peers with lived experience of mental health service provision and specifically the CJS emerged as a consistent theme in the design and delivery of effective practice innovations in the literature reviewed (Mooney et al., 2019). Indeed, this aspect of service design and delivery was specifically noted by Lord Bradley in his follow-up report of 2014 into the reforms needed to support people with mental health problems and learning disabilities in the justice system, where he recommended:

‘the adoption of a more psychosocial model of care to recognise the multiple and complex nature of need and a move towards recovery orientated approaches with a greater role for current and former service users (‘experts by experience’) in designing and delivering care’ (Durcan et al., 2014).

The inclusion of people with lived experience of mental health services in the development of peer crisis services is identified by SAMHSA (2014) as a key component of crisis services at Intercept 0. For example, emergency department diversion can consist of a triage service, embedded mobile crisis, or a peer specialist who provides support to people in crisis. Within the UK, bespoke services, often including peers with lived experience, have been established to divert and safely manage people with acute alcohol intoxication away from A&E. These include Alcohol Intoxication Management Services (AIMS), Drunk Tanks, Safe Havens, and Alcohol Treatment Centres (ATCs) (see Irving et al., 2018). One UK survivor-led crisis service project, Dial House in Leeds, provides services to people in acute mental health crisis with frequent occurrence of repeat self-harm and suicidality (See Venner, 2009).

However, notwithstanding these notable initatives, the inclusion of peers with lived experience in service delivery across all sectors remains in development.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted key messages for service providers and policy makers arising from a selective review of practice innovations which sought to apply the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) to the Northern Ireland criminal justice context (Mooney et al., 2019). The SIM is noted as a trauma-informed approach which highlights opportunities to divert justice-involved children and adults with complex needs from the CJS and thus improve their life chances.

The key messages are consistent with many UK policy developments and initiatives. For example, the Female Offender Strategy (Ministry of Justice, 2018) promises a focus on early intervention, community-based solutions, and better custody for those women who have to be in prison, while a cross-government Victims Strategy (2018) notes the intention to develop the use of ‘trauma-informed approaches to support female offenders who are also victims’. In recent years England has rolled out Family Drug and Alcohol Courts (FDAC) – serving 36 local authorities as an alternative to standard care proceedings in the circumstances of parental drug or alcohol misuse – with positive effect (Papaioannou et al., 2023). In Northern Ireland, there has also been piloting of mental health courts and mental health triage (NIAO, 2019, p.40-41). The Improving Health within Criminal Justice Strategy and Action Plan (June 2019) recognised that many young people and adults who come into contact with the CJS have a history of under-utilising health and social care services and consequently have unmet needs. Contact with the CJS is therefore recognised as ‘an important opportunity to engage or re-engage such children, young people and adults with the services they need’ with the intention that providing ‘the right care and treatment may have a positive impact in terms of reducing re-offending’ (Department of Health and Department of Justice, 2019, p.ii). Such goals are coherent with those of the SIM.

While the prevalence rates of complex needs in the justice-involved population are indeed significant, with issues not easily separated or addressed, this paper highlights that with concerted cross-system collaborative efforts, there are opportunities to make positive contributions to improving the life chances of children, young people and adults by ensuring early access to the most appropriate health and social care services to meet identified needs and divert from sustained involvement in the justice system.

References

Abreu, D., Parker, T.W., Noether, C.D., Steadman, H.J. and Case, B. (2017). ‘Revising the paradigm for jail diversion for people with mental and substance use disorders: Intercept 0’, Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 35(5-6), pp. 380-395.

Anders, P., Jolley, R. and Leaman, J. (2017). A resource for Directors of Public Health, Police and Crime Commissioners, the police service and other health and justice community service providers and users. Revolving Doors, the Home Office and Public Health England.

Akin, B.A., Strolin-Goltzman, J. and Collins-Camargo, C. (2017). ‘Successes and challenges in developing trauma-informed child welfare systems: A real-world case study of exploration and initial implementation’, Children and Youth Services Review, 82, pp. 42-52.

Baker, J., Berzins, K. and Kendal, S. (2022). Reducing restrictive practices across health, education and criminal justice settings. Report: University of Leeds.

Bellis, M.A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Perkins, C. and Lowey, H. (2014). ‘National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England’, BMC Medicine, 12(1), pp. 1-10.

Bellis, M.A., Ashton, K., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Bishop, J. and Paranjothy, S. (2015). ‘Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the Welsh adult population’, Public Health Wales, 36, pp. 1-36.

Bonfine, N. and Nadler, N. (2019). ‘The Perceived Impact of Sequential Intercept Mapping on Communities Collaborating to Address Adults with Mental Illness in the Criminal Justice System’, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, pp. 1-11.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., Davidson, G. and Forbes, T. (2018a). Developing trauma informed practice in Northern Ireland: The child welfare system. Belfast: Safeguarding Board NI.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., Davidson, G. and Forbes, T. (2018b). Developing trauma informed practice in Northern Ireland: The education system. Belfast: Safeguarding Board NI.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., Davidson, G. and Forbes, T. (2018c). Developing trauma informed practice in Northern Ireland: The justice system. Belfast: Safeguarding Board NI.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., Davidson, G. and Forbes, T. (2018d). Developing trauma informed practice in Northern Ireland: The health and mental health care systems. Belfast: Safeguarding Board NI.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., Davidson, G. and Forbes, T. (2018e). Developing trauma informed practice in Northern Ireland: Key Messages. Belfast: Safeguarding Board NI.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D. and Davidson, G. (2019b). Trauma informed child welfare systems—A rapid evidence review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2365.

Cusack, P., McAndrew, S., Cusack, F. and Warne, T. (2016). ‘Restraining good practice: reviewing evidence of the effects of restraint from the perspective of service users and mental health professionals in the United Kingdom (UK)’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 46, pp. 20-26.

Dallaire, D. H. (2007). ‘Incarcerated mothers and fathers: A comparison of risks for children and families’, Family Relations, 56(5), pp. 440-453.

Department of Health and Department of Justice, (2019). Improving Health within Criminal Justice: A strategy and action plan to ensure that children young people and adults in contact with the criminal justice system are healthier, safer and less likely to be involved in offending behaviour. DoH and DoJ.

DeMatteo, D., LaDuke, C., Locklair, B.R. and Heilbrun, K. (2013). ‘Community-based alternatives for justice-involved individuals with severe mental illness: Diversion, problem-solving courts, and reentry’, Journal of Criminal Justice, 41(2), pp. 64-71.

D'Souza, S., Lane, R., Jacob, J., Livanou, M., Riches, W., Rogers, A., ... and Edbrooke-Childs, J. (2021). ‘Realist Process Evaluation of the implementation and impact of an organisational cultural transformation programme in the Children and Young People's Secure Estate (CYPSE) in England: study protocol’, BMJ open, 11(5), e045680.

Durcan, G., Saunders, A., Gadsby, B. and Hazard, A. (2014). The Bradley Report five years on: An independent review of progress to date and priorities for future development. The Bradley Commission and Centre for Mental Health. Available at: http://www.mentalhealthchallenge.org.uk/library-files/MHC151-Bradley_report_five_years_on.pdf

Farmer, M. (2017). The Importance of Strengthening Prisoners' Family Ties to Prevent Reoffending and Reduce Intergenerational Crime. Ministry of Justice.

Farmer, M. (2019). The Importance of Strengthening Female Offenders’ Family and other Relationships to prevent Reoffending and reduce Intergenerational Crime. Ministry of Justice.

Farrington, D.P., Barnes, G.C. and Lambert, S. (1996). ‘The concentration of offending in families’, Legal and Criminological Psychology, 1(1), pp. 47-63.

Gains Action Brief (2019). Data Collection Across the Sequential Intercept Model: Essential Measures, SAMHSA GAINS Center. PEP19-SIM-DATA.

Gray, P., Smithson, H. and Jump, D. (2021). Serious youth violence and its relationship with adverse childhood experiences, HM Inspectorate of Probation Academic Insights 2021/13. Available at: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2021/11/Academic-Insights-Gray-et-al.pdf

Heilbrun, K., Mulvey, E., DeMatteo, D., l Schubert, C. and Griffin, P. (2015) ‘Key Aspects of Applying the Sequential Intercept Model and Future Challenges’ (Chapter 15), in P. Griffin, K. Heilbrun, E. Mulvey, D. DeMatteo and C. Schubert (eds.) Criminal justice and the sequential intercept model: Promoting community alternatives for individuals with serious mental illness. New York: Oxford.

Irving, A., Goodacre, S., Blake, J., Allen, D. and Moore, S.C. (2018). ‘Managing alcohol-related attendances in emergency care: can diversion to bespoke services lessen the burden?’, Emergency Medicine Journal, 35(2), pp. 79-82.

HM Inspectorate of Probation (2020). Accommodation and support for adult offenders in the community and on release from prison in England. Manchester: HM Inspectorate of Probation.

Kerig, P.K., Becker, S.P. and Egan, S. (2010). ‘From internalizing to externalizing: Theoretical models of the processes linking PTSD to juvenile delinquency’, in S.J. Egan (ed.) PTSD: Causes, symptoms and treatment (pp. 33–78). Hauppauge, NY: Nova.

Kilkelly, U. (2023). Evidence-based core messages for youth justice, HM Inspectorate of Probation Academic Insights 2023/09. Available at: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/10/Academic-Insights-Evidence-based-core-messages-for-youth-justice-by-Professor-Ursula-Kilkelly-Final.pdf

Ko, S.J., Ford, J.D., Kassam-Adams, N., Berkowitz, S.J., Wilson, C., Wong, M., ... and Layne, C.M. (2008). ‘Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice’, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(4), 396.

Kubiak, S., Covington, S. and Hillier, C. (2017). ‘Trauma-informed corrections’, in D. Springer and A. Roberts (eds.) Social work in juvenile and criminal justice system, 4th edition. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Lang, J.M., Ake, G., Barto, B., Caringi, J., Little, C., Baldwin, M.J., Sullivan, K., Tunno, A.M., Bodian, R., Stewart, C.J. and Stevens, K. (2017). ‘Trauma screening in child welfare: lessons learned from five states’, Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(4), pp. 405-416.

Markson, L., Losel, F., Souza, K., and Lanskey, C. (2015). ‘Male prisoners’ family relationships and resilience in resettlement’, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 15(4), pp. 423-441.

Mauer, M. and Chesney-Lind, M. (eds.) (2002). Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment. New York: The New Press.

May C., Sharma N. and Stewart D. (2008), Factors linked to reoffending: a one-year follow-up of prisoners who took part in the Resettlement Surveys 2001, 2003 and 2004. London: Ministry of Justice.

Miller, E.A., Green, A.E., Fettes, D.L. and Aarons, G.A. (2011). ‘Prevalence of maltreatment among youths in public sectors of care’, Child maltreatment, 16(3), pp. 196-204.

Ministry of Justice (2018). Female offender strategy. London: Ministry of Justice. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/female-offender-strategy

Ministry of Justice (2019a). Youth Justice Statistics 2017-18. London: Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice (2019b). Safety in custody quarterly update to December 2018. London: Ministry of Justice.

Mooney, S., Bunting, L., Coulter, S. and Montgomery, L. (2019). Applying the Sequential Intercept Model to the Northern Ireland Context: A Selective Review of Practice Innovations to improve the Life Chances of justice-involved young people and adults with complex needs. Belfast: Safeguarding Board for Northern Ireland and Queen’s University Belfast. Available at https://www.safeguardingni.org/resources/applying-sequential-intercept-model-ni-context-full-reportpdf

Munetz, M.R., and Griffin, P.A. (2006). ‘Use of the Sequential Intercept Model as an Approach to Decriminalization of People with Serious Mental Illness’, Psychiatric Services, 57 (4), pp. 544–549.

Northern Ireland Audit Office (2019). Mental health in the criminal justice system. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, NIAO.

Papaioannou, K., Kuo, T., Dimova, S. et al. (2023). Evaluation of Family Drug and Alcohol Courts. Foundations, the What Works Centre for Children and Families.

Pickens, I. (2016). ‘Laying the groundwork: Conceptualizing a trauma-informed system of care in juvenile detention’, Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(3), pp. 220-230.

Policy Research Associates (2018). The Sequential Intercept Model: Advancing Community-Based Solutions for Justice-involved People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders. Policy Research Associates. Available at: https://www.prainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/SIM-Brochure-Redesign0824.pdf

Prison Reform Trust (2023). Bromley Briefings Prison Factfile (January 2023). Prison Reform Trust.

Public Health England (2018). Policing and Health Collaboration in England and Wales. Landscape Review. London: Public Health England.

Quigg, Z., Wallis, S. and Butler, N. (2018). Routine Enquiry about Adverse Childhood Experiences Implementation pack pilot evaluation (final report). Public Health Institute: Liverpool John Moore’s University.

Shaw, J., Conover, S., Herman, D., Jarrett, M., Leese, M., McCrone, P., and Stevenson, C. (2017). ‘Critical time Intervention for Severely mentally ill Prisoners (CrISP): a randomised controlled trial’, Health Services and Delivery Research, 5(8).

Trotter, C. (2021). Collaborative Family Work in Youth Justice, HM Inspectorate of Probation Academic Insights 2021/02. Available at: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2021/02/Collaborative-Family-Work-in-Youth-Justice-KM2.pdf

Venner, F. (2009). Risk Management in a survivor-led crisis service. Mental Health Practice, 13(4), 18-22. Available at: https://www.lslcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Mental-Health-Practice-Risk-Management-in-a-Survivor-Led-Crisis-Service-Dec-2009.pdf

Willison, J.B., McCoy, E.F., Vasquez-Noriega, C. and Travis Reginal, T. with Parker, T. (2018) Using the Sequential Intercept Model to Guide Local Reform an Innovation Fund Case Study, Urban Institute. Washington D C. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/using-sequential-intercept-model-guide-local-reform

Yuan, Y. and Capriotti, M.R. (2019). ‘The impact of mental health court: A Sacramento case study’, Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(4), pp. 452-467.

© Crown copyright 2024

You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or email psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk.

Where we have identified any third-party copyright information, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available for download at: www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation

Published by:

HM Inspectorate of Probation

1st Floor Civil Justice Centre

1 Bridge Street West

Manchester

M3 3FX

The HM Inspectorate of Probation Research Team can be contacted via HMIProbationResearch@hmiprobation.gov.uk

ISBN: 978-1-916621-19-0

| Type of Resource |

|

|---|---|

| Publication Date | |

| Committee/Panel |

|

| Audience |

|

| Tags |

|

- Academic Insights - Mooney et al (Jan 24 final).pdfDownload PDF

- Academic Insights - Mooney et al (Jan 24 final).docxDownload DOCX

- Academic Insights - Mooney et al (Jan 24 final).odtDownload ODT